Student Curatorial Exhibition/// ‘Hot Air:’ developed in response to ‘Men Gather, in Speech…’ Cooper Gallery, 2015

Exhibitions Student Curatorial Team members Kirsten Mae Wallace, Eilidh Wilson, Fiona Morag McKinnon, Alison Kay and Aylson Stewart share their reflections after collaborating on Hot Air: Cooper Gallery Project Space, 16-20 February, 2015. The exhibition was devised in response to Men Gather, in Speech… the concurrent film exhibition in Cooper Gallery, Jan-Feb, 2015.

After putting a call out to the Cooper Gallery Student Curatorial Team our small group of 5 was formed. Within a couple of meetings we had formed our proposal. We worked well as a team and our idea and concept was reached quickly.

The idea was to each view art from the 3 artists that would feature in the Men Gather, in Speech… exhibition and to form a sentence that encapsulates their work. In order to make sure that we did not make the art that we wanted to purely because it appealed to us we then passed our sentence on to the next person. We decided not to share our sentences with the whole team because we thought that might affect the work we created. This was a great introduction to working collaboratively because, although we were working as part of a team, we each individually created our clips.

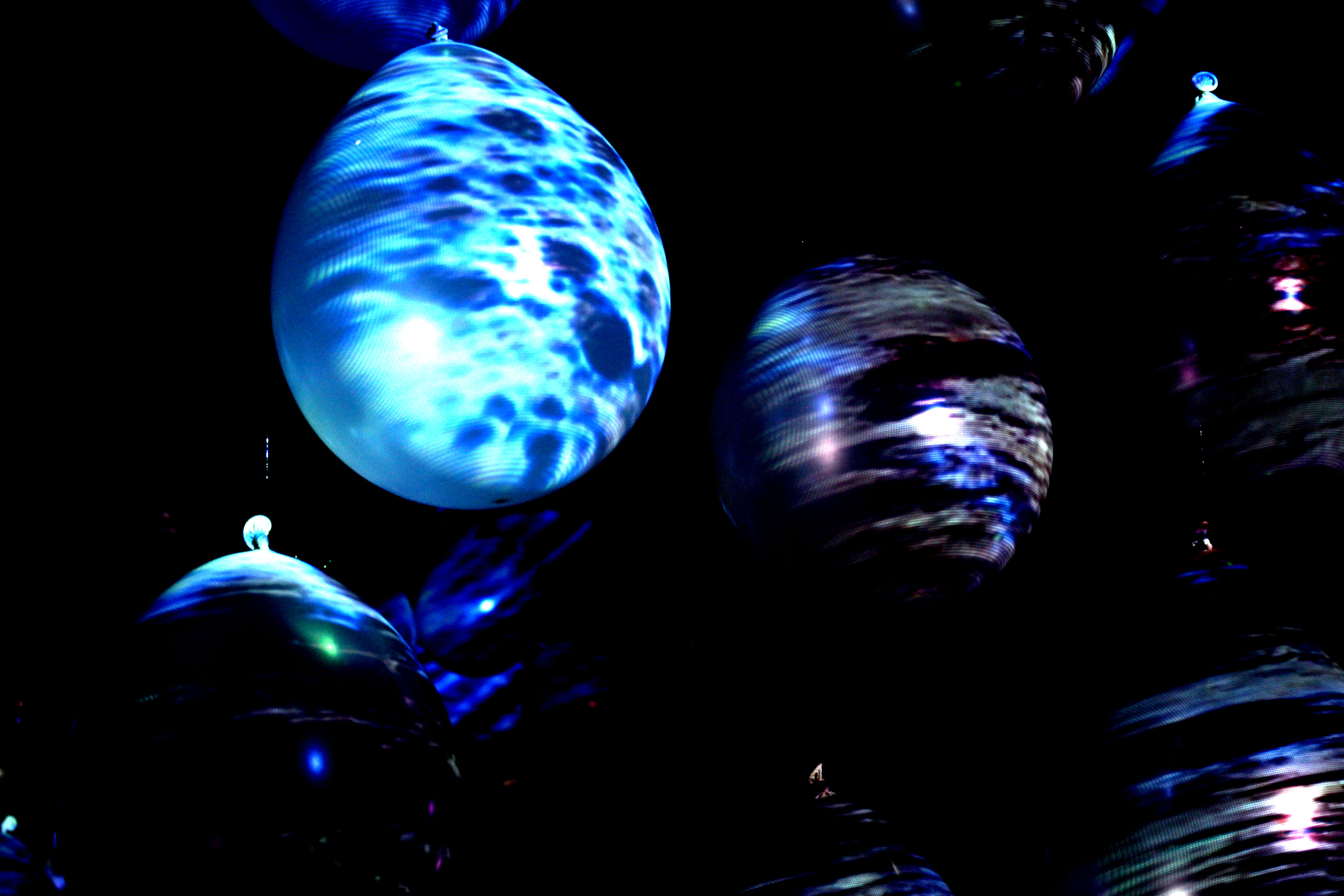

Projecting onto balloons abstracted and tied our work together into one cohesive unit. Without the balloons the project would not have worked so well. I think, for all of us, the balloons worked far better than we had ever imagined. The projection was visible through the balloons and this added an extra dimension we had not expected. The balloons, the layout and the viewers interaction with them was for me the strongest part of this project.

“A visual exploration of consequential effects caused by the loss of information or a misread signal, in the breakdown of communication between human individuals; where wires have been crossed.”

Sentence by Kirsten Wallace 4th Year Fine Art Student

“This exhibition was extremely challenging as it was a collection of firsts for me. I am a direct entry student in to level 2 Fine Art. I have never; worked collaboratively, in film, made a proposal or worked as part of the Student Curatorial Team before.

I lacked confidence and knowledge when it came to collecting and creating the film clips that I was going to show in the exhibition. This was highlighted in the fact that I failed to remove the sound in my clips. If I had more time and experience I would have added audio to my work. I will experiment with this further in the future. My confidence lay in the materials and installation of the exhibition. I was an active member in bringing us together as a team and keeping the momentum going.

This project highlighted my strengths and weaknesses. It gave me a deeper understanding of what goes into putting on an exhibition and what needs to be considered. Our attention mainly lay in the production of the videos and the installation giving little time for marketing, budgeting and organizing all the other parts that make up an exhibition. The dull stuff is equally as important as the fun stuff.

We have talked about doing this exhibition again at a different venue. With working knowledge of how the clips and balloons work together it would give us a chance to better optimize our marketing and organizing skills. Watch this space; it might soon be filled with Hot Air.”

Ally Kay

“Fighting the noise, to be heard, only fills the silence with more noise.”

Sentence by Ally Kay 2nd year Fine Art Student

“I saw this opportunity as means to expand my studio practice and work within the Student Curatorial Team. I am studying my masters with a focus on art practice but come from a humanities background so being given quite a specific brief to work from made the whole process much easier.

The sentence I was given really resonated with me and I looked into the struggles of my own past as inspiration. I found the process of making the video difficult and very cathartic, although was ultimately happy with the outcome.

I do feel that due to other commitments towards installation of the exhibition meant that I was not fully involved in the process and did not help the dynamic in the team. It was a steep learning curve for all of us and having gone through the experience I would definitely look more at the logistics (marketing, budgets etc.) of everything and not get as absorbed by the actual making of the piece.

All in all I greatly enjoyed the experience and would gladly do it again soon, although with the new knowledge gained.”

Aylson Stewart

“Something to do with monologue, a picture of humanity?”

Sentence by Aylson Stewart

“I found taking on this project as a new means of gathering everything I have learned over the years and putting it into practice by being part of an exhibition. As a 4th year student, I thought it was important to challenge myself and see how the ideas that I am exploring in my work for degree show can be taken into different contexts.

The sentence I was given set off a number of ideas, but after having went to the opening talk with Rose English, I felt inspired to recreate a work I had made in 2nd year and incorporate it into the video.

Putting on the exhibition for me, was a great means of realising timescale. Time for mistakes and technical issues should always be factored into self-set deadlines. Also, realising the importance of PR, for me creating the poster was a big learning curve for me, helping me to realise that was looks good on a screen does not necessarily look good on paper. Overall we worked well as a group, despite several setbacks for everyone and given the timeframe what we put together was a successful.”

Eilidh Wilson

“Routine is the ultimate form of distraction. Blind to the words that may break it.”

Sentence by Eilidh Wilson

“Throughout the past four years studying Art, Philosophy and contemporary practices, my ideas and interests have grown and developed through both critical and practical practice. It is this which was the foundation of my enthusiasm to take part in this collaborative project. Responding to men Gather, In Speech…, we decided to work in the medium of digital film. I feel that this experience has aided my personal practice greatly, for I currently work in this medium.

This exhibition was a steep learning curve for me. It gave me an insight into collaborative exhibitions, and of the problems that arise during installing exhibitions. Our team worked very well together, and it was an incredibly rewarding experience. Despite a few technical set-backs, the installation was successful and received a very positive response at the opening night. Overall, I feel that this project has provided a stepping-stone for me to continue my engagement with curatorial practice.”

Fiona Morag McKinnon

“Interdisciplinary exploration concerning the moments of human subjectivity which normally pass unnoticed; a view from a different perspective.”

Sentence by Fiona Morag McKinnon

“I was interested in this opportunity to create art work as a group in response to Men Gather, in Speech… as the call out was centrally revolved around moving image, which is currently the medium I am working with in my own practice. I have been looking for the chance to work in a collaboration for a while so I saw this as a perfect opportunity and decided to meet with other members of the Student Curatorial Team who were beginning to put forward some very interesting ideas. We had a very productive first meeting and it was apparent we were all on the same wavelength.

I was happy with the sentence I received from Fiona shortly after this meeting and found it a very helpful starting point in creating film scenes – which I wanted to draw upon beauty in the every day. I enjoy video editing and piecing scenes together but always struggle with gathering the film footage, so having this brief to work on and respond to has proven to be a useful way of working. Having set deadlines and others relying upon my input also helps.

I enjoyed the process of installing the balloons and found that we worked particularly well together during this install. The balloons looked fantastic once the projection was up and running, and it hit various angles which made for some interesting photographic documentation. I learned which parts of my own film worked well and which scenes did not. Strong colours and patterns worked very well on the balloons, as did text and parts of the body. However bright, fast paced movements in my own film was difficult to make out. We could distinguish connections throughout our films which we had not intended and overall I thought the exhibition was visually, a great success.

We had a great turnout on our opening night and I had some interesting conversations with both peers on my course and students I hadn’t met before, who each had very positive feedback on our interactive projection. At the very beginning of this process, I thought a week would be a good length for this exhibition, but soon discovered how quickly the week went by and that some people were unable to make it along in that time. I think we pulled off a fantastic original idea and worked well together under a tight timeline with some unforeseen obstacles. It has been a learning curve for me and is my first official collaborative exhibition which I was proud to be a part of and hope it will be the first of many. I am excited at the prospect of developing Hot Air further and hope that we do decide to propose to exhibit again at different locations in the future.”

Kirsten Mae Wallace

Coinciding with Roman Empire: Power and People, Classical Art: the Legacy of the Ancients illustrates ancient Greek and Roman culture through a dynamic contrast of paintings, sculptures, screen-prints, ceramics and drawings. Drawn from Dundee’s collection of fine art, the artworks embody the mythical influences of the ancient Greeks and the Romans. The ancient Greeks’ focus on figures and form has laid the foundations for much of figurative art today. It is this combined focus, alongside an affinity to mythology, which engenders the creative depictions of heroes and gods within their work.

Coinciding with Roman Empire: Power and People, Classical Art: the Legacy of the Ancients illustrates ancient Greek and Roman culture through a dynamic contrast of paintings, sculptures, screen-prints, ceramics and drawings. Drawn from Dundee’s collection of fine art, the artworks embody the mythical influences of the ancient Greeks and the Romans. The ancient Greeks’ focus on figures and form has laid the foundations for much of figurative art today. It is this combined focus, alongside an affinity to mythology, which engenders the creative depictions of heroes and gods within their work.

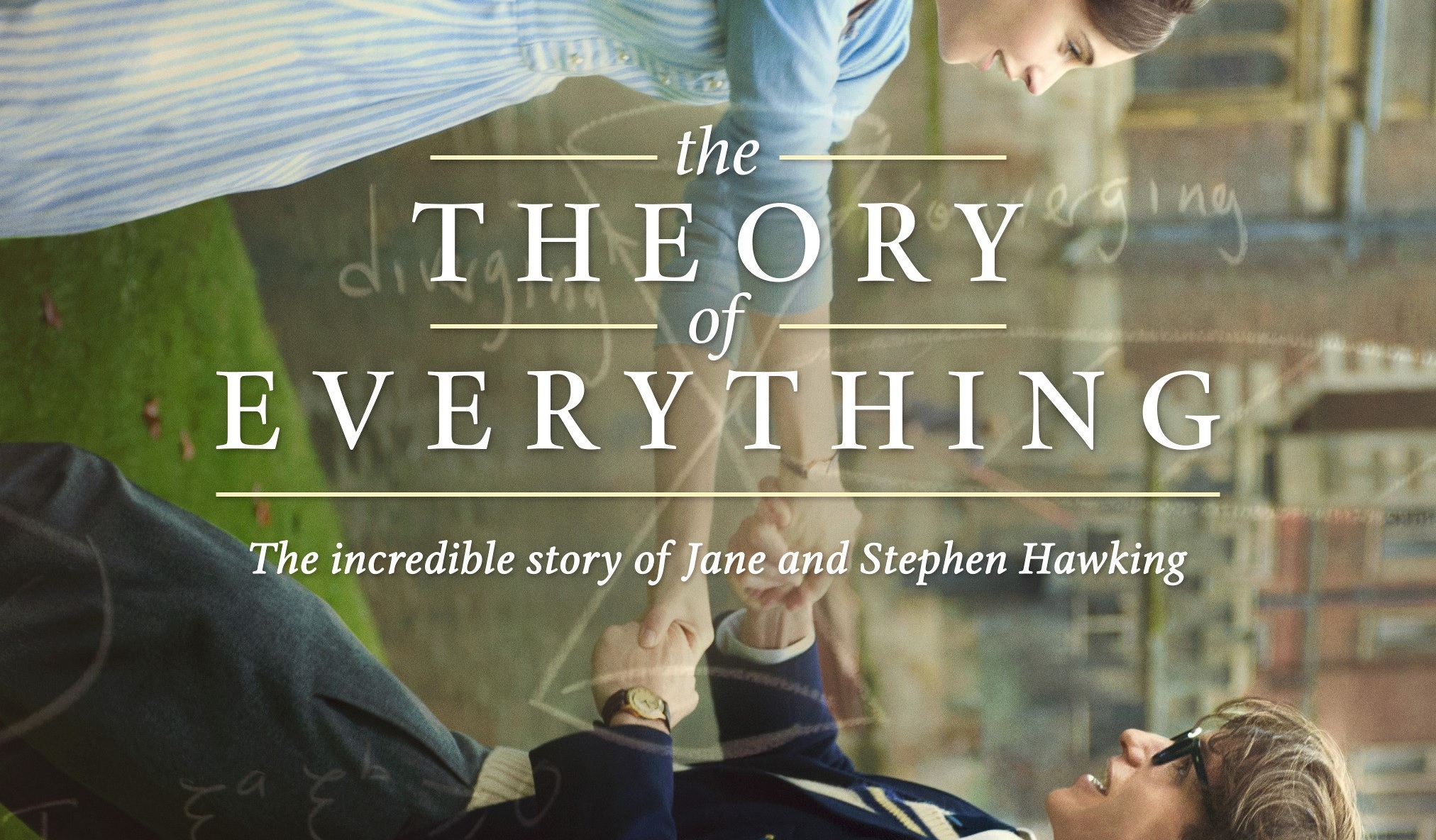

The Theory of Everything is a compelling film, adapted from Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen by Jane Wilde Hawking. The intimate workings behind Stephen Hawking’s genius are glossed over, in this instance focusing instead upon his personal life. It is an evocative portrayal of Hawking’s struggles with MND (Motor Neuron Disease), offering a glimpse into the gradual decline of his motor functions, the strain that this placed on his relationship with his wife Jane (Felicity Jones), and his unyielding perseverance in the face of adversity.

The Theory of Everything is a compelling film, adapted from Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen by Jane Wilde Hawking. The intimate workings behind Stephen Hawking’s genius are glossed over, in this instance focusing instead upon his personal life. It is an evocative portrayal of Hawking’s struggles with MND (Motor Neuron Disease), offering a glimpse into the gradual decline of his motor functions, the strain that this placed on his relationship with his wife Jane (Felicity Jones), and his unyielding perseverance in the face of adversity.